First Peoples

It is hard to find the sweet spot when thinking about “first peoples.”

We can easily make caricatures of them by projecting our image of them as having all of the virtues we lack. They must have been unselfish, not needing to own the land. They must have been close to nature and peace loving—all unlike today’s generation, obsessed with greed and violence, and quite unlike our rapacious, European ancestors.

Of course, this is all a reaction against the attitudes of our rapacious ancestors themselves, who justified their own land grabs by dismissing those who were living here already as soulless savages.

It is heartening to see many institutions now ready to declare that their tall buildings are built on tribal lands of the past. The only snag in this thought is that we wind up naming one or two tribes who were here when our rapacious ancestors first came, conveniently airbrushing out countless other “tribes” or “nations” or “civilizations” that preceded them for the past 13,000 years.

And, from what I can tell as a rank amateur historian of the various people’s who set foot on the ground that is at this moment Heatherhope Farm, I would say they possessed many of the very same values and vices that mark modern Americans. They trod softly on the land because there were very few of them, and they moved with the animals they depended on for food, clothing, and shelter. They were close to the land because that was almost the entirety of the world they lived in. They wasted little when they had to and much when they could. They were peace loving when they had to and war like when they could.

But they were certainly not soulless savages. They developed wonderful technology, including metallurgy, that suited their situation, and a philosophy of life fed by complex oral traditions.

It was a near total disregard for the deep history and complex culture of native Americans that drove European immigrants to these shores to impoverish themselves and despoil a whole continent’s land and people. Native peoples, because they depended on nature’s ways, had developed a host of healthy strategies to balance their appetite with the ability of nature to provide. And through the centuries before Europeans arrived they had worked out means to settle disputes without massive bloodshed, resulting in the vast numbers of tribes and interlocking clans. Europeans came with a dream of conquering nature, an arrogance about the superiority of their own culture, and a massive, all absorbing appetite to go with their massive numbers. The white folk also came and painted the landscape with blood because they used the native peoples as pawns in the wars imported from Europe. Small, inter-tribal conflicts faded into much bloodier wars and the counting of scalps.

Heatherhope 18,000 to 10,000 Years Ago (Possibly earlier)

It is only the most recent scholarship that has begun to throw off the Euro-centric point of view so that we can explore this land’s very ancient history. And very recent finds in the study of archaeology and DNA analysis shows that these first peoples—first immigrants to the land we live on--made this continent home far earlier than we had ever thought possible.

About all scholars can agree about is that the very first of the “first peoples” of the Americas were themselves immigrants. They first came over the Bering Land Bridge between Siberia and North America as much as 20,000 and not less than 18,000 years ago. Archaeologists point out that fossilized footsteps in White Sands New Mexico, campfire remains in Mexico, and bone tools in the Yukon of Canada have been dated to over 20,000 years ago. They made their way through gaps in the ice shield and possibly by water craft, hugging the North Pacific coast, and then slowly migrated over generations from the north to the west, southwest, and further on to Central and South America. As the last of the huge glaciers, covering most of what is now Canada, down to the majority of what is now Illinois slowly withdrew, Heatherhope Farm’s location, along with Northern Illinois, would opened to become part of just seven or so concentrations of sites of Paleo Indians in North America, located in steppe, or unforested grassland.

So the very first humans (PaleoIndians) to set foot on dry—not ice-covered—land on Heatherhope, would have been 10,000 to 18,000 years ago—possibly earlier. They would have been people of the Clovis culture who migrated from the south of the continent. One of the most intriguing finds has been the Meadowcroft Rockshelter in southwestern Pennsylvania, which may have been continually inhabited for more than 19,000 years. This was a material culture that predates what used to be thought of as the oldest in North America—the Clovis. Archaeologists have found little chips of their fluted Clovis knives and spear points in various digs in Michigan—dated as early as 18,000 years ago. But the glaciers covering our location in northern Illinois may have persisted until about 13,000 years ago.

Any who walked over Heatherhope would have traveled by foot in pursuit of such migratory animals of the cold, wet landscape as caribou and mastodon. They may have stopped to gather edible plants, butcher and clean the meat, scrape the hides of their prey, and resharpen their tools. It is interesting to think of the ridge that runs across Heatherhope may have provided the high and dry ground for these activities, at the edge of what is now known as the south branch of the Kishwaukee River.

While prehistoric Heatherhope was strategically situated for hunting in a vast grassland, the Great Lakes and the vast web of rivers and streams were also vital for transportation. Gradually the Clovis culture, which stalked the megafauna such as the mammoth and mastodon, gave way to the short-lived Folsom culture as those large mammals became extinct. Then the Folsom gave way a few thousand years later (by about 10,000 years ago) to other cultures as their key prey animal, the bison antiques became extinct. That animal was up to 25% larger than today’s bison.

Already we have a dissonance with the popular idealization of native peoples. It is probable that these extinctions were the product not just of the climate becoming dryer and warmer, but of increased human competition for food and over hunting. Being “close to nature” didn’t keep the “first peoples” from overkill if they had the means. And well into the 19th century CE the plains Indians were herding buffalo over cliffs, killing off far more than they could eat or use for hides.

10,000 to 3,000 Years Ago

After the Paleo Indian age came the Archaic Period, from 8,000 to 1000 BCE. Human foot-traffic on Heatherhope’s prehistoric landscape would still have been extremely infrequent but growing gradually. These people would have begun to take part in increasing trade that was developing all over the continent, and especially with more organized and settled peoples to Heatherhope’s south (today’s Louisianna and Florida), and a bit west, near the Mississippi River. The people’s around Heatherhope were less organized and so less stratified and so did not partake in the practice of honoring the elite dead by building mounds. Visitors here would have traded their furs for copper tools and decorations from the Lake Superior region, and woven baskets from the south. As the climate warmed there was more dependence on smaller game like deer, and plentiful nuts and grains. Late in this era the cultivation of grain crops, and pottery making, spread northward from Mesoamerica and begin to become widespread in the Eastern woodlands of America, but it was not until the very end of the Archaic period that these advances began to be adopted by the people around Heatherhope who remained almost exclusively hunter-gatherers.

3,000 to 374 Years Ago

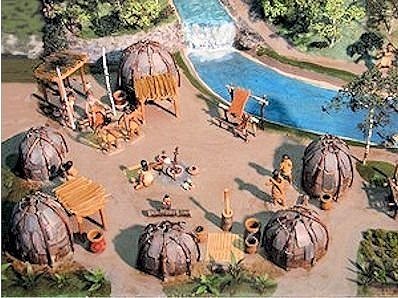

The Post-archaic period, followed, from 1000 BCE till European contact. Illinois and Heatherhope would have been a meeting point or overlap of holdover hunter-gatherer ways leftover from the Archaic period, and the agriculturalist Mississipian culture further south. Indidans of the Northern Illinois area would have been of the Woodland culture, even if they were living in grasslands in this far western extent of the cultural area. Those who trod across Heatherhope in this period would have followed the seasons for their hunting and gathering--travelling by both canoe on the rivers and by foot. They very slowly developed better stone and bone tools, leather and textile crafting, and some cultivation of foods. They would have used spears and some spear throwing atlatls until upgrading to bows and arrows nearer the end of this period. They gradually became more adept at making their own pottery, and at cultivating just a few plants such as goosefoot, sunflower, marsh elder, and squash. But their diet was predominantly the meat from deer, beaver, raccoon, and bear, and the wild plants such as hickory and acorn nuts, wild berries, wild grapes, and berries.

From 100 BCE to 500 CE Heatherhope’s land would have been near the northern range of the Havana Hopewell culture that began along the Ohio and Illinois Rivers, and later thrived along the Illinois River and Mississippi River Valleys of Iowa, Illinois, Indiana, southwest Michigan, southern Wisconsin, Minnesota, and Missouri. It was, at heart, a system of interaction between a variety of societies and cultures. The people who trod Heatherhope would have enjoyed items from as far afield as the Yellowstone area to the west, and the Gulf coast.

The people who trod this place from about 1,500 to 1,000 years ago would have been part of the Late Woodland period. More, but smaller villages were being built. The construction of burial mounds decreased a great deal, along with the long-distance trade in exotic materials. The bow and arrow replaced the spear and spear-thrower atatl, and more cultivation of maize, beans, and squash took place. Again, there may well have been over hunting of large game animals because of the effectiveness of the bow and arrow, and this, along with the volcanic activity of 535-536, which contributed to a cooling of the climate, may have led to the breakup of tribes.

In these ancient times the land made the people rather than the people making the land around Heatherhope. The land was prairie but also wetland. Hunting and gathering was dominant, but cultivating crops was also possible, spawned by the cultivation based culture called Mississippian. This overlap of Woodland and Mississippian culture would have defined the times the natives of this area lived in as the first Europeans arrived.

The Mississippian culture started as early as 800 CE and lasted until the Europeans arrived in this area in the 17th century. It was centered along the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers and the rivers and streams that flow into it. Around Heatherhope the Mississippian built off of the Hopewell culture, continuing to build effigy and burial earthen mounds. The growing of crops, including maize intensified, and trade networks expanded. It was small villages and decentralized chiefdoms that prevailed in northern Illinois, but these natives would have benefited a small by some trade and sharing technology with the farm more organized Mississippians. While small villages and decentralized chiefdoms prevailed around Heatherhope, 250 miles to the south was Cahokia, in Illinois, near present day St. Louis, the most populous settlement in North America before the European, number about 20,000 by it’s peak in the 13th century.

But by the time of the arrival of the very first Europeans near Heatherhope this complex and vital Mississippian culture was already in decline. In fact, the entire native population of North America was in decline because of the diseases brought by Hernando de Soto already in the 1540s. De Soto, and his Spanish expedition, wandered all over the American Southeast for years before arriving in Mexico a fraction of its original size. This expedition and others brought previously unknown European and African diseases to the New World. While smallpox was the worst killer, they also brought new influenza strains, measles, whooping cough, chicken pox, bubonic plague, typhus, and malaria. Scientists estimate that between 80 and 90 percent of the native North American population died in epidemics within the first century and a half of the arrival of Columbus in 1492. Students of Indian history estimate that there were well over 1,000 Native American civilizations in North America, while today only 574 are recognized by the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Thus, of course, the tribal life of Indians that might have made Heatherhope home, or hunting ground, was also severely disrupted.

The written history of Illinois begins in the summer of 1673. On May 17 of that year, French explorers Louis Jolliet, Father Jacques Marquette, and five other French-Indian voyageurs, or fur traders, left St. Ignace, Michigan with two canoes, paddled to Green Bay, Wisconsin, then upstream, or southward on Wisconsin’s Fox River to the site of present day Portage, Wisconsin. They portaged two miles through marsh and oak forest to the Wisconsin River. By June 17 they had reached the Mississippi near present day Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin. Then, on June 20 they reached present day Illinois, near Galena, about 95 miles west by northwest of Heatherhope. Of course, by this start of European written history, the real story of European/Indian interaction was in full swing. Fur trading voyageurs and other French explorers were already hard at work creating trade links and some settlements and even forts to protect their trade.

I dwell on the details of the Jolliet-Marquette expedition a bit nostalgically because my own father grew up in Ely, Minnesota, the heart of the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness, and started me out in a love for canoeing and this history of the voyageurs and their hard, hard lives. But I also wanted to point out how the Indians of the Great Lakes region used the lakes, rivers, and streams as we would today’s system of Interstates and other roads.

Jolliet and Marquette and their team continued down the Mississippi until, at the mouth of the Arkansas, they were convinced the big river continued to the Gulf of Mexico, at which point they feared violent encounters with Spanish colonists. On the way back up the Mississippi they met natives who told them of a shorter route to Lake Michigan via what is now known as the Illinois River. Taking this to the Des Plaines they could portage into the Chicago River to Lake Michigan. By the time Marquette reached a mission at the southern end of Green Bay, and Joliette returned to Quebec, the latter had lost all his records when his canoe overturned in rapids. But he wrote his recollections down from memory, and they were in agreement with Marquette’s. And so the written history of these first, friendly encounters between Indians and White men in the land of Heatherhope began.

The first of the Indian groups that Jolliet and Marquette met along the Illinois section of the Mississippi was the Illinois, or Illiniwek—a collection of twelve chiefdoms that occupied that river valley on the western edge of today’s Illinois. These French frontiersmen estimated that the total population of the Illinois Confederacy was 12,000 to 13,000.

It was the second group, the Miami tribe, that lived in small villages south and west of Lake Michigan, including around Heatherhope. During the next couple of centuries, however, the territory of the Illinois Confederacy shrank, and the Miami moved eastward, opening the whole of the state to other tribes, and the region around Heatherhope to the Fox, Sauk, and the “Council of the Three Fires”: the Potawatomi, Odawa (Ottawa), and Ojibwa—that long-term alliance against the Iroquois Confederacy of the east, and the Sioux of the west and north. It would be the Potawatomi who would be the tribe of the Heatherhope area of the 17th and 18th centuries, and that would meet the first substantial European settlers in the 19th century.

According to their own memories these last three tribes came down from the north as a single tribe, to arrive in the upper region of Lake Huron in ancient times, before splitting into three separate peoples. Perhaps the Potawatomi were driven by conflicts from their home on the lower peninsula of Michigan to that state’s Upper Peninsula and near Green Bay, Wisconsin because of pressure from the Iroquois confederacy who were fighting to dominate the fur trade. In the latter part of the 1600s, because of continued conflicts over furs, they migrated south and along the Milwaukee River near present day Milwaukee.

It seems apparent that Indian tribes were no less and no more motivated by economic gain than white settlers, and no more or less prone to resort to violence to further their economic strength. And so, the Potawatomi record of alliances in warfare also reveals tendency to perhaps weigh pragmatism over principle, and then suffer negative consequences when their bets didn’t pay off. They sided with the French in their wars against the Iroquois during the Beaver Wars of the 17th century (the North American front of the European Seven Years’ War between France and the United Kingdom), before they retreated to the area around Green Bay. Then, following the American Revolution, in the late 1780s, the Potawatomi, along with their Three Fires Council partners, the Ojibwa and the Odawa, joined a loose alliance with Little Turtle of the Miami, and other tribes—all of which had been progressively pushed west by the relentless encroachments by land hungry Europeans. They fought a number of small skirmishes with settlers and a militia from Kentucky, then won a series of larger battles with the United States military with the help of the British. But the British were afraid of fighting a two front war with the French and United States, backed away from their alliance with the Indians, and the Indians were decisively beaten at the Battle of Fallen Timbers in NW Ohio. The result was the Treaty of Greenville of 1795 by which the Indian confederacy ceded most of the state of Ohio and significant portions of what would become the states of Indiana, Illinois, and Michigan. The Potawatomi themselves retained their claims to the land around the Great Lakes but ceded three strategic locations in Illinois to the United States: the portage connecting the Chicago and Des Plaines Rivers, the land at the mouth of the Illinois River, and the mouth of the Chicago River, where the United States established Fort Dearborn in 1803.

Thus, by the beginning of the 1800s, the territory of Potawatomi still enveloped most of the country surrounding the lower third of Lake Michigan (parts of present day Wisconsin, Illinois, Indiana, and Michigan), though their population at this time was possibly never over 3,000.

The Potawatomi were an important part of the Shawnee warrior, Tecumseh’s Confederacy and war against the United States in the Indiana Territory that continued through the War of 1812. But then, throughout the following Sixty Years War for control of the Great Lakes region, they switched alliances between the United States and the United Kingdom, calculating the impact on their trade and land interests.

Within a generation, President Andrew Jackson and his Indian Removal Act of 1830 triggered the series of made and broken treaties that amounted to the US government policy of ethnic cleansing or forced displacement of American Indian tribes from their homelands in the eastern United States to lands west of the Mississippi. This amoral policy was inspired and accelerated by a combination of the greed for land and gain by real estate speculators and settlers, and by the consequent promise of power and flow of cash to ambitious politicians. When the government broke every promise they made, they idea of “Manifest Destiny” was invented to soothe consciences. We had a moral duty to God to act immorally to the Indians because this was God’s plan for us.

Act one of this series of government sponsored swindles of the Potawatomi was the infamous Treaty of St. Louis of 1804. William Henry Harrison, the governor of the Indiana Territory, which included present day Illinois, was pressured by U.S. President Thomas Jefferson to secure land from the Native Americans. When the Sauk and Fox tribes grew resentful of the way they were treated by the U.S. government, and a few Sauk hunters murdered and scalped four settlers who had entered their territory, it gave Harrison the opportunity he was looking for. The Sauk chiefs denounced the murders, but American officials immediately demanded the surrender of the murderers and that the Sauk enter into negotiations for a resolution. The Sauk tribal council sent a delegation of five chiefs and at least one Fox leader to resolve the issue and obtain the release of their captive hunters. Though the Indian delegation was not authorized to sell any land, though they in no way understood what they were agreeing to, and though they did not indeed inhabit much of the land under negotiation, the American officials connived to a treaty which they claimed the Sauk and Fox sold a huge swath of land from northeast Missouri, almost all of Illinois north of the Illinois River, and a large section of southern Wisconsin—all for $2,234.50 and an annuity of $600 for the Sauk and $400 for the Fox. The Sauk and Fox renounced the treaty and became so alienated from the U.S. government that they supported the British in the War of 1812.

The next and final great act in this immoral removal of the Great Lakes Indian tribes, including the Potawatomi, came as a direct result of that awful Treaty of St. Louis. The Sauk leader Black Hawk, in April, 1832, returned with a band of Sauk, Fox, and Kickapoo from Indian Territory in Iowa Indian Territory to fight for the right to remain in their ancestral lands.

The Potawatomi were pressured to contribute warriors to this effort, some, along with neighboring Ho-Chunk ids, but by in large the great majority of Potawatomi realized they were no match for the growing numbers of white settlers and militia, and refused to fight. In one incident only a couple months before the end of general hostilities, a band of Potawatomis, with the help of three Sauk, killed fifteen settlers in an intractable dispute over a dam the settlers built that prevented the fish from reaching the Potawatomi village. This Indian Creek Massacre happened, about 30 miles of Heatherhope. But after the war three Potawatomi were arrested and tried, but acquitted for lack of evidence.

Black Hawk and his band were immediately opposed by a militia. They tried to parley under a flag of truce, but were fired upon, so turned on the poorly trained militia at the Battle of Stillman’s Run, about 30 miles northwest of Heatherhope. The skirmish left about a dozen militia dead, and perhaps a few Sauk, but the event sealed the fate of thousands of Indians and triggered the final removal of Indian civilization from the Great Lakes region. There was a brief outburst of attacks on forts and colonies by frustrated Indians. Black Hawk’s band retreated into Wisconsin, gravely weakened by disease, hunger, starvation, and desertion, as they were pursued by the militia. At the Battle of Bad Axe, along the Mississippi, 200 miles northwest of Heatherhope.

Once again it was the monstrous machine of greed for power and gain and raw vengeance that proved treacherous for the Indians. The frontier effort to push first peoples west of the Mississippi was a populist cause just as it wins votes today to pledge to deport undocumented immigrants. The “other” is always seen as enemy, not compatriot. A host of men with political ambitions fought against Black Hawk and his band: at least seven future Senators, four future governors of Illinois, future governors of Michigan, Nebraska and the Wisconsin Territory, and future U.S. Presidents, Zachary Taylor and Abraham Lincoln.

Black Hawk’s band of 400 to 500 men, women and children had tried to signal that they only wanted to cross back over the Mississippi and return to Indian Territory. When they tried to cross the river in rafts they were stopped by a steamboat. Blackhawk tried to surrender, but soldiers could not understand him. Some warriors were killed and others took cover for a two-hour firefight. A couple dozen Indians were killed, including a 19 year old woman shot through the arm of the child she was holding. The next day the militia and regular soldiers pushed Black Hawk’s band toward the river, while a steamboat pressed them there in eight hours of what the newspapers called a massacre. Native women and children fled to the river and many drowned. The soldiers killed everyone who ran for cover or tried to cross the river. More than 150 were killed at the scene, most were scalped by the soldiers, and 75 more Native Americans were captured. Across the river the Dakota Sioux, in league with the U. S. Army, brought 68 scalps and 22 prisoners to the U.S. Indian agent. The U.S. suffered five killed and 19 wounded.

Black Hawk and many of the other leaders of his band were not killed in this battle of Bad Axe, August 1-2, 1832, but escaped north to the La Crosse River. But there they surrendered on August 27. In fact, they were paraded for political purposes throughout the East.

The Black Hawk War marked the end of Native armed resistance to U.S. expansion and Indian removal. In quick succession American officials pressured the Ho-Chunks, Sauk, and Fox to sign over their lands east of the Mississippi and south of the Wisconsin River for small annuities and bits of land in Indian Territory, ever further west of the Mississippi.

Because the Potawatomi had not fought against the U.S., but actually helped them during the Black Hawk War, officials did not seize their land. But it took only a year for U.S. officials to pressure the remaining Potawatomi to sell up and move west or north. In the Treaty of Chicago of September, 1833 the government made the Ojibwa, Odawa and Potawatomi an “offer they could not refuse.” They were required to turn over to the United States five million acres of land, including reservations in Illinois, Wisconsin Territory, and Michigan Territory, and, within the next few years, the tribe splintered. Some moved to Canada, some to far northern Wisconsin, others to Missouri and Kansas. In the 1840s, with money they received for their Illinois lands, they bought a 30 square mile reservation in Kansas Territory, about 30 miles north of whwat is now Topeka. Potawatomi communities remaining in present-day Ohio were forced to move to Louisiana, which was then controlled by Spain.

There is one tragic figure of the Potawatomi removal that has come back to haunt or bless us in these latter days. That is Shabbona (1775-1859). He was born into the Odawa tribe but became a chief among the closely related Potawatomi, and lived in a village just 19 miles southwest of Heatherhope.

As a chief, Shabbona led some warriors to fight with Tecumseh, resisting white settlement, fighting with the British and against the Americans in the War of 1812; but by 1815 he began to come to the aid of the Americans against a brief uprising of Winnebago in Wisconsin. In 1829 he was awarded a grant of 1,280 acres of wooded land by the American government in appreciation for his cooperation. Later, during the Black Hawk War he cemented his good relations with the Americans by not leading his warriors in support of Black Hawk, and even warning white settlers of impending attacks, and guiding white militia in several of their marches.

When most of the Potawatomi from Illinois moved to Kansas in those years between 1833 and 1839, Chief Shabonna and about 20 to 30 of his clan stayed behind on his allotment 19 miles southwest of Heatherhope. Then, in 1850 the chief and his people took a trip to Kansas to visit his relatives. After several weeks he returned to his reserve in Illinois to find that his house had been moved and white settlers were living in it, and that all of 1,280 acres had been auctioned off by the General Land Office because he had abandoned it.

But today, after 174 years, the Prairie Band Potawatomi, descendents of the Potawatomi of Heatherhope, and of the Shabbona reserve, have had some success in reclaiming the land that was, in effect, stolen from them. They paid nearly $10 million to buy back 130 acres of their original land, along with two homes, and had it put in trust on April 19, 2024 by the U.S. Department of the Interior, making this land the only federally recognized Tribal Nation in Illinois.

An Illlinois House Bill 4718, is now being considered that would authorize the state to hand over what is now Shabbona Lake and State Park, located on the reserve land illegally auctioned off in 1850, to the Prairie Band Potawatomi for $1. It also allows the tribe and the Department of Natural Resources to enter into a land management agreement under which the land would remain open to the public for recreational use for an unspecified period. The bill was advanced by eight Democratic representatives over the objections of four Republicans. Now it must be considered by the Illinois House and Senate.

It seems that the ghost of Chief Shabbona, along with the ghosts of the Potawatomi who lived in a small village just 1000 yards east of Heatherhope, in a grove of trees along the south branch of the Kishwaukee River, and the ghosts of the millions of Native Americans killed by disease, squeezed by settlers, hounded by militias, and robbed of their rightful inheritance by the combined national machineries of France, Britain, and the United States, are stirring, just a few miles from this farm.